Responding to change

The problem facts used to create a solution may change before or during the execution of that solution. Delaying planning in order to lower the risk of problem facts changing is not ideal, as an incomplete plan is preferable to no plan.

The following examples demonstrate situations where planning solutions need to be altered due to unpredictable changes:

-

Unforeseen fact changes

-

An employee assigned to a shift calls in sick.

-

An airplane scheduled to take off has a technical delay.

-

One of the machines or vehicles break down.

Unforeseen fact changes benefit from using backup planning.

-

-

Cannot assign all entities immediately

Leave some unassigned. For example:

-

There are 10 shifts at the same time to assign but only nine employees to handle shifts.

For this type of planning, use overconstrained planning.

-

-

Unknown long term future facts

For example:

-

Hospital admissions for the next two weeks are reliable, but those for week three and four are less reliable, and for week five and beyond are not worth planning yet.

This problem benefits from continuous planning.

-

-

Constantly changing problem facts

Use real-time planning.

More CPU time results in a better planning solution.

Timefold Solver allows you to start planning earlier, despite unforeseen changes, as the optimization algorithms support planning a solution that has already been partially planned. This is known as repeated planning.

1. Backup planning

Backup planning adds extra score constraints to create space in the planning for when things go wrong. That creates a backup plan within the plan itself.

An example of backup planning is as follows:

-

Create an extra score constraint. For example:

-

Assign an employee as the spare employee (one for every 10 shifts at the same time).

-

Keep one hospital bed open in each department.

-

-

Change the planning problem when an unforeseen event occurs.

For example, if an employee calls in sick:

-

Delete the sick employee and leave their shifts unassigned.

-

Restart the planning, starting from that solution, which now has a different score.

-

The construction heuristics fills in the newly created gaps (probably with the spare employee) and the metaheuristics will improve it even further.

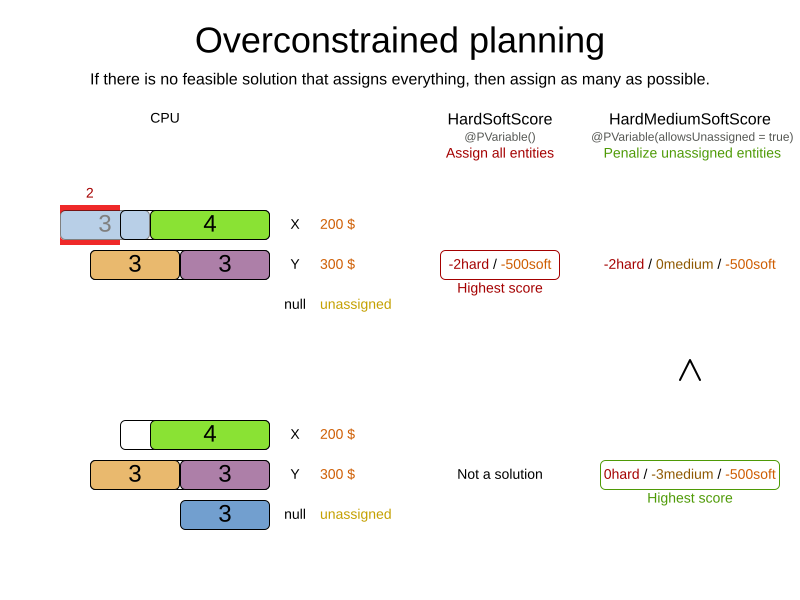

2. Overconstrained planning

When there is no feasible solution to assign all planning entities, it is preferable to assign as many entities as possible without breaking hard constraints. This is called overconstrained planning.

By default, Timefold Solver assigns all planning entities, overloads the planning values, and therefore breaks hard constraints. There are two ways to avoid this:

-

Use planning variables with unassigned values, so that some entities are unassigned.

-

Add virtual values to catch the unassigned entities.

2.1. Overconstrained planning with null variable values

If we handle overconstrained planning with null variable values, the overload entities will be left unassigned:

To implement this:

-

Add a score level (usually a medium level between the hard and soft level) by switching

Scoretype. -

Make the planning variable allow unassigned values.

-

Add a score constraint on the new level (usually a medium constraint) to penalize the number of unassigned entities (or a weighted sum of them). Use

forEachIncludingUnassignedand check if the planning variable or inverse relation shadow variable isnull:

-

Java

private Constraint penalizeUnassignedVisits(ConstraintFactory factory) {

return factory.forEachIncludingUnassigned(Visit.class)

.filter(visit -> visit.getVehicle() == null)

.penalize(HardMediumSoftScore.ONE_MEDIUM)

.asConstraint("Unassigned Visit");

}2.2. Overconstrained planning with virtual values

If we handle overconstrained planning with virtual values, the overload entities will be assigned to one or more dummy values provided by the user.

|

This method is inferior to overconstrained planning with |

To implement this:

-

Add a score level (usually a medium level between the hard and soft level) by switching

Scoretype. -

Add a number of virtual values. It can be challenging to determine a good formula to calculate that number:

-

Do not add too many, as that will decrease solver efficiency.

-

Importantly, do not add too few as that will lead to an infeasible solution.

-

-

Add a score constraint on the new level (usually a medium constraint) to penalize the number of virtual assigned entities (or a weighted sum of them).

-

Optionally, change all soft constraints to ignore virtual assigned entities.

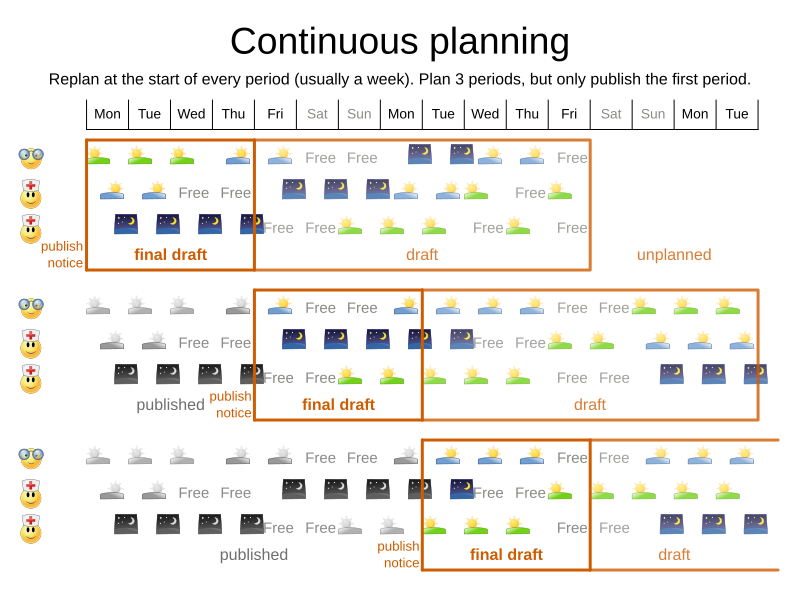

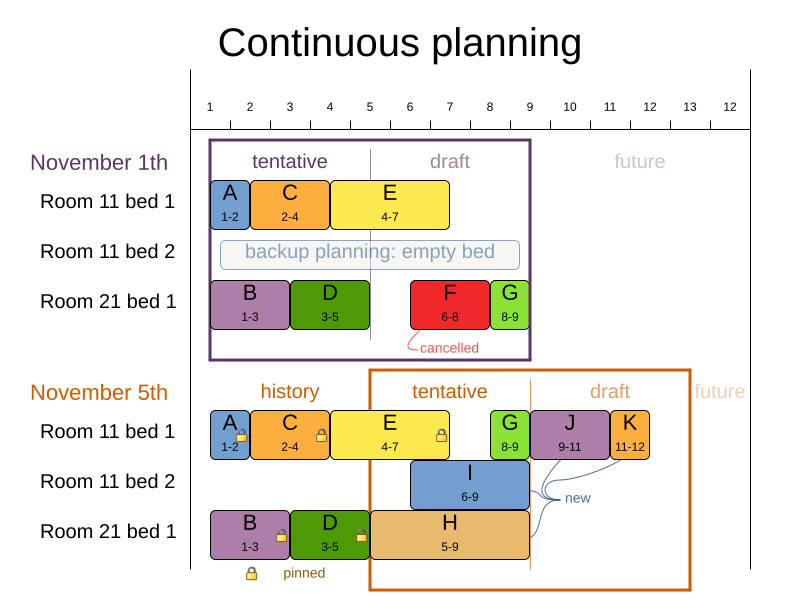

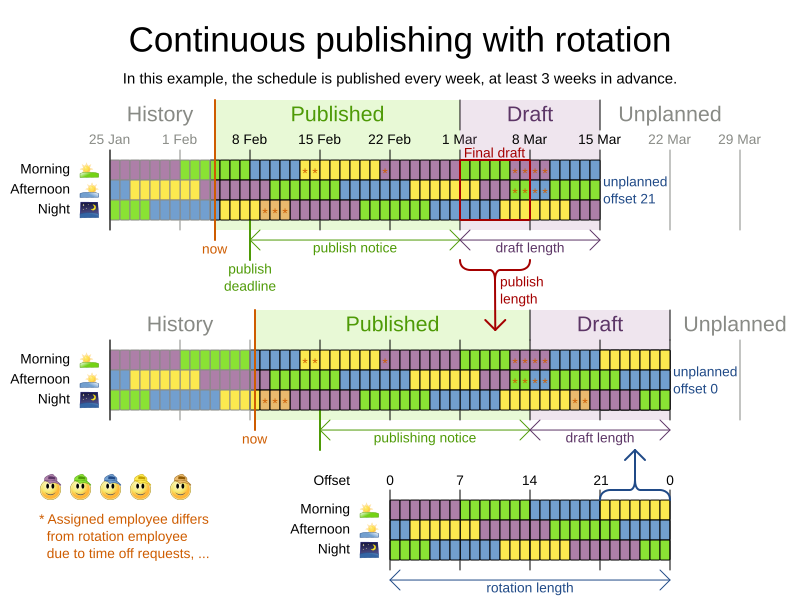

3. Continuous planning (windowed planning)

Continuous planning is the technique of planning one or more upcoming planning periods at the same time and repeating that process monthly, weekly, daily, hourly, or even more frequently. However, as time is infinite, planning all future time periods is impossible.

In the employee rostering example above, we re-plan every four days. Each time, we actually plan a window of 12 days, but we only publish the first four days, which is stable enough to share with the employees, so they can plan their social life accordingly.

In the bed allocation scheduling example above, notice the difference between the original planning of November 1st and the new planning of November 5th: some problem facts (F, H, I, J, K) changed in the meantime, which results in unrelated planning entities (G) changing too.

The planning window can be split up in several stages:

-

History

Immutable past time periods. It contains only pinned entities.

-

Recent historic entities can also affect score constraints that apply to movable entities. For example, in employee rostering, an employee that has worked the last three historic weekends in a row should not be assigned to three more weekends in a row, because he requires a one free weekend per month.

-

Do not load all historic entities in memory: even though pinned entities do not affect solving performance, they can cause out of memory problems when the data grows to years. Only load those that might still affect the current constraints with a good safety margin.

-

-

Published

Upcoming time periods that have been published. They contain only pinned and/or semi-movable planning entities.

-

The published schedule has been shared with the business. For example, in employee rostering, the employees will use this schedule to plan their personal lives, so they require a publish notice of for example 3 weeks in advance. Normal planning will not change that part of schedule.

Changing that schedule later is disruptive, but were exceptions force us to do them anyway (for example someone calls in sick), do change this part of the planning while minimizing disruption with non-disruptive replanning.

-

-

Draft

Upcoming time periods after the published time periods that can change freely. They contain movable planning entities, except for any that are pinned for other reasons (such as being pinned by a user).

-

The first part of the draft, called the final draft, will be published, so these planning entities can change one last time. The publishing frequency, for example once per week, determines the number of time periods that change from draft to published.

-

The latter time periods of the draft are likely change again in later planning efforts, especially if some of the problem facts change by then (for example employee Ann can’t work on one of those days).

Despite that these latter planning entities might still change a lot, we can’t leave them out for later, because we would risk painting ourselves into a corner. For example, in employee rostering, we could have all our rare skilled employees working the last 5 days of the week that gets published, which won’t reduce the score of that week, but will make it impossible for us to deliver a feasible schedule the next week. So the draft length needs to be longer than the part that will be published first.

-

That draft part is usually not shared with the business yet, because it is too volatile and it would only raise false expectations. However, it is stored in the database and used as a starting point for the next solver.

-

-

Unplanned (out of scope)

Planning entities that are not in the current planning window.

-

If the planning window is too small to plan all entities, you’re dealing with overconstrained planning.

-

If time is a planning variable, the size of the planning window is determined dynamically, in which case the unplanned stage is not applicable.

-

3.1. Pinned planning entities

A pinned planning entity doesn’t change during solving. This is commonly used by users to pin down one or more specific assignments and force Timefold Solver to schedule around those fixed assignments.

3.1.1. Pin down planning entities with @PlanningPin

To pin some planning entities down, add an @PlanningPin annotation on a boolean getter or field of the planning entity class.

That boolean is true if the entity is pinned down to its current planning values and false otherwise.

-

Add the

@PlanningPinannotation on aboolean:-

Java

@PlanningEntity public class Lecture { private boolean pinned; ... @PlanningPin public boolean isPinned() { return pinned; } ... } -

In the example above, if pinned is true,

the lecture will not be assigned to another period or room (even if the current period and rooms fields are null).

| Planning pin value must never change during planning. To change whether an entity is pinned or not, use ProblemChange |

3.1.2. Pinning a planning list variable

There are cases where pinning only a part of planning list variable is necessary. For example, if some customer visits have already happened but are still in the list, it makes sense to pin them down.

To achieve that, use a @PlanningPinToIndex annotation instead:

-

Java

@PlanningEntity

public class Vehicle {

...

@PlanningListVariable

protected List<Customer> customers = ...; // Includes some customers.

@PlanningPinToIndex

protected int firstUnpinnedIndex = 1;

...

}When @PlanningPinToIndex is used, the list is split in two parts.

-

The first part, with indexes less than

firstUnpinnedIndex, is pinned. In the example above, it means that the first element of the list can not be moved from its position. Nothing will be added before it, and it will not be removed from the list. It will forever stay as the first element of the list. -

The second part, starting with

firstUnpinnedIndexand ending where the list ends, is movable. Items can be freely added, removed and reordered in this part of the list.

This means that, if the @PlanningPinToIndex is zero (0), the list is fully modifiable.

Consequently, if the @PlanningPinToIndex is equal to the size of the list,

all the contents of the list are pinned,

but the list can still be extended by adding to the end of the list.

To pin the entire list, preventing any modifications to the list whatsoever,

@PlanningPin needs to be used on the entity itself.

| Value of the index must never change during planning. To change how far the list is pinned, use ProblemChange. |

3.1.3. Configure a PinningFilter

PinningFilter is deprecated for removal in a future version of Timefold Solver.

Use @PlanningPin as described above.

|

Alternatively, to pin some planning entities down,

add a PinningFilter that returns true if an entity is pinned,

and false if it is movable.

For example, on the employee scheduling quickstart:

public class ShiftPinningFilter implements PinningFilter<EmployeeSchedule, Shift> {

@Override

public boolean accept(EmployeeSchedule employeeSchedule, Shift shift) {

ScheduleState scheduleState = employeeSchedule.getScheduleState();

return !scheduleState.isDraft(shift);

}

}Configure the PinningFilter:

@PlanningEntity(pinningFilter = ShiftPinningFilter.class)

public class Shift {

...

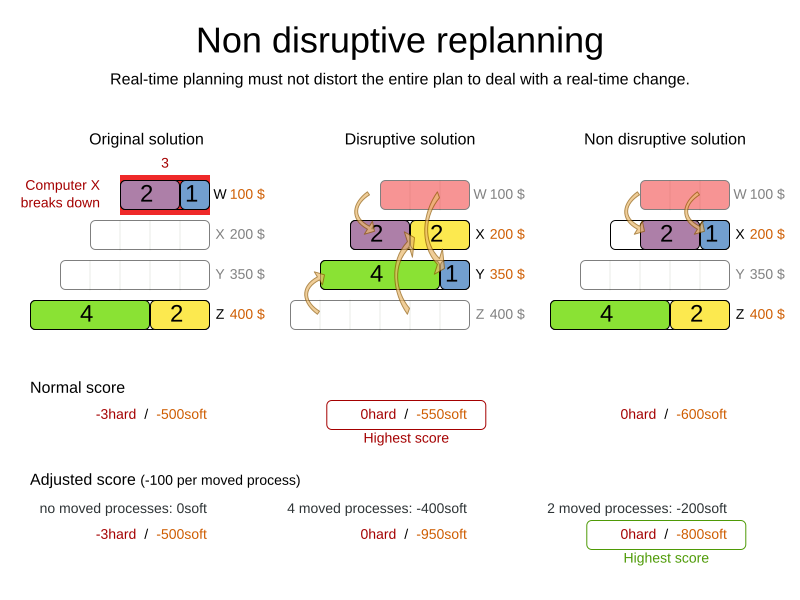

}3.2. Nonvolatile replanning to minimize disruption (semi-movable planning entities)

Replanning an existing plan can be very disruptive. If the plan affects humans (such as employees, drivers, …), very disruptive changes are often undesirable. In such cases, nonvolatile replanning helps by restricting planning freedom: the gain of changing a plan must be higher than the disruption it causes. This is usually implemented by taxing all planning entities that change.

In conference scheduling, the entity has both a planning variable timeslot and its original value publishedTimeslot:

-

Java

@PlanningEntity

public class Talk {

...

@PlanningVariable

private Timeslot timeslot;

private Timeslot publishedTimeslot;

...

}During planning, the planning variable timeslot changes.

By writing a constraint comparing it with the publishedTimeslot, a change in plan can be penalized:

-

Java

Constraint publishedTimeslot(ConstraintFactory factory) {

return factory.forEach(Talk.class)

.filter(talk -> talk.getPublishedTimeslot() != null

&& talk.getTimeslot() != talk.getPublishedTimeslot())

.penalize(HardSoftScore.ofSoft(1000))

.asConstraint("Published timeslot");

}By configuring a penalty weight of -1000 we can express that a solution will only be accepted

if it improves the soft score for at least 1000 points per variable changed (or if it improves the hard score).

4. Real-time planning

To do real-time planning, combine the following planning techniques:

-

Backup planning - adding extra score constraints to allow for unforeseen changes.

-

Continuous planning - planning for one or more future planning periods.

-

Short planning windows.

This lowers the burden of real-time planning.

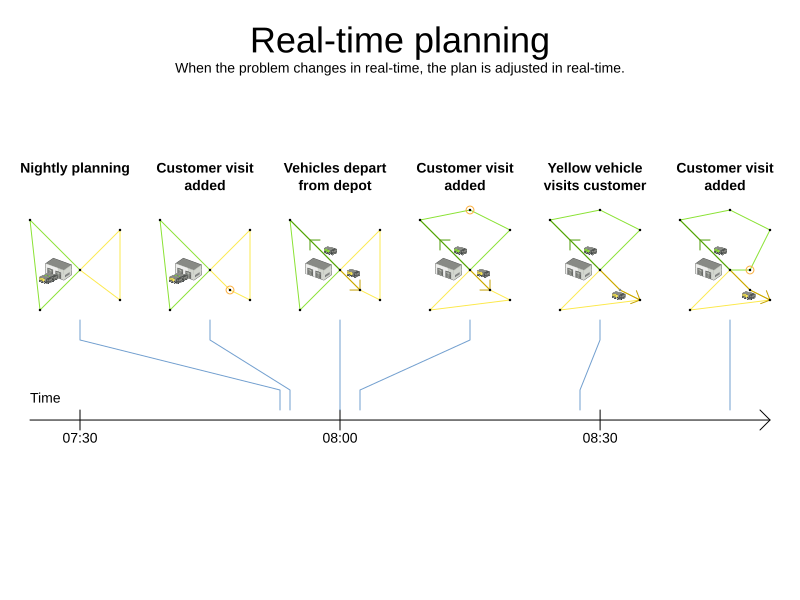

As time passes, the problem itself changes. Consider the vehicle routing use case:

In the example above, three customers are added at different times (07:56, 08:02 and 08:45), after the original customer set finished solving at 07:55, and in some cases, after the vehicles have already left.

Timefold Solver can handle such scenarios with ProblemChange (in combination with pinned planning entities).

4.1. ProblemChange

While the Solver is solving, one of the problem facts or planning entities may be changed by an outside event.

For example, an airplane is delayed and needs the runway at a later time.

|

Do not change the problem fact instances used by the |

Add a ProblemChange to the Solver, which it executes in the solver thread as soon as possible.

For example:

-

Java

public interface Solver<Solution_> {

...

void addProblemChange(ProblemChange<Solution_> problemChange);

boolean isEveryProblemChangeProcessed();

...

}Similarly, you can pass the ProblemChange to the SolverManager:

-

Java

public interface SolverManager<Solution_, ProblemId_> {

...

CompletableFuture<Void> addProblemChange(ProblemId_ problemId, ProblemChange<Solution_> problemChange);

...

}and the SolverJob:

-

Java

public interface SolverJob<Solution_, ProblemId_> {

...

CompletableFuture<Void> addProblemChange(ProblemChange<Solution_> problemChange);

...

}Notice the method returns CompletableFuture<Void>, which is completed when a user-defined Consumer accepts

the best solution containing this problem change.

-

Java

public interface ProblemChange<Solution_> {

void doChange(Solution_ workingSolution, ProblemChangeDirector problemChangeDirector);

}|

The |

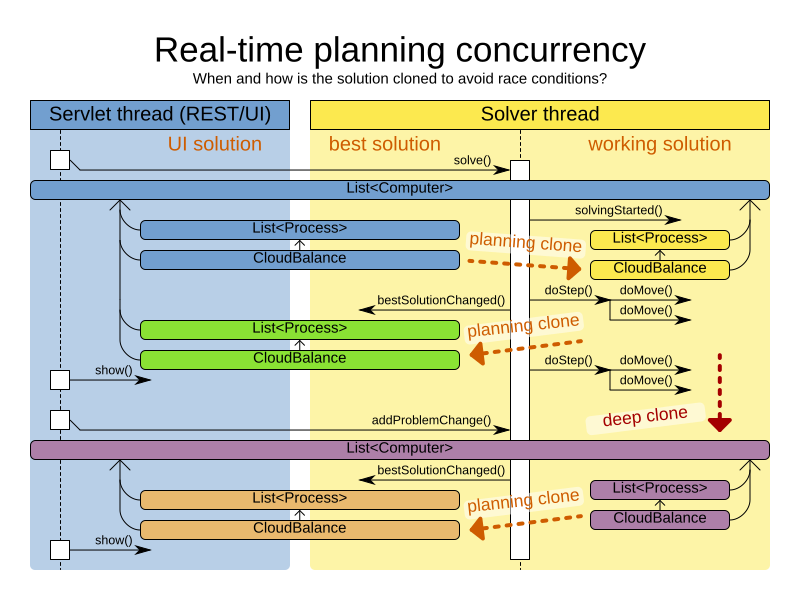

To write a ProblemChange correctly,

it is important to understand the behavior of a planning clone.

A planning clone of a solution must fulfill these requirements:

-

The clone must represent the same planning problem. Usually it reuses the same instances of the problem facts and problem fact collections as the original.

-

The clone must use different, cloned instances of the entities and entity collections. Changes to an original Solution entity’s variables must not affect its clone.

When implementing problem changes, consider the following:

-

Any change in a

ProblemChangemust be done on the@PlanningSolutioninstance ofscoreDirector.getWorkingSolution(). -

The

workingSolutionis a planning clone of theBestSolutionChangedEvent'sbestSolution.-

The

workingSolutionin theSolveris never the same solution instance as in the rest of your application: it is a planning clone. -

A planning clone also clones the planning entities and planning entity collections.

Thus, any change on the planning entities must happen on the

workingSolutioninstance passed to theProblemChange.doChange(Solution_ workingSolution, ProblemChangeDirector problemChangeDirector)method.

-

-

Use the method

ProblemChangeDirector.lookUpWorkingObject()to translate and retrieve the working solution’s instance of an object. This requires annotating a property of that class as the @PlanningId. -

A planning clone does not clone the problem facts, nor the problem fact collections. Therefore the

workingSolutionand thebestSolutionshare the same problem fact instances and the same problem fact list instances.Any problem fact or problem fact list changed by a

ProblemChangemust be problem cloned first (which can imply rerouting references in other problem facts and planning entities). Otherwise, if theworkingSolutionandbestSolutionare used in different threads (for example a solver thread and a GUI event thread), a race condition can occur. -

For performance reasons, it is recommended to submit problem changes in batches. To do that, use

addProblemChanges(List<ProblemChange>)method instead ofaddProblemChange(ProblemChange).

4.1.1. Cloning solutions to avoid race conditions in real-time planning

Many types of changes can leave a planning entity uninitialized, resulting in a partially initialized solution. This is acceptable, provided the first solver phase can handle it.

All construction heuristics solver phases can handle a partially initialized solution, so it is recommended to configure such a solver phase as the first phase.

The process occurs as follows:

-

The

Solverstops. -

Runs the

ProblemChange. -

restarts.

This is a warm start because its initial solution is the adjusted best solution of the previous run.

-

Each solver phase runs again.

This implies the construction heuristic runs again, but because little or no planning variables are uninitialized (unless you have a planning variable with unassigned values), it finishes much quicker than in a cold start.

-

Each configured

Terminationresets (both in solver and phase configuration), but a previous call toterminateEarly()is not undone.Terminationis not usually configured (except in daemon mode); instead,Solver.terminateEarly()is called when the results are needed. Alternatively, configure aTerminationand use the daemon mode in combination withBestSolutionChangedEventas described in the following section.

4.2. Daemon: solve() does not return

In real-time planning, it is often useful to have a solver thread wait when it runs out of work, and immediately resume solving a problem once new problem fact changes are added.

Putting the Solver in daemon mode has the following effects:

-

If the

Solver'sTerminationterminates, it does not return fromsolve(), but blocks its thread instead (which frees up CPU power).-

Except for

terminateEarly(), which does make it return fromsolve(), freeing up system resources and allowing an application to shutdown gracefully. -

If a

Solverstarts with an empty planning entity collection, it waits in the blocked state immediately.

-

-

If a

ProblemChangeis added, it goes into the running state, applies theProblemChangeand runs theSolveragain.

To use the Solver in daemon mode:

-

Enable

daemonmode on theSolver:<solver xmlns="https://timefold.ai/xsd/solver" xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance" xsi:schemaLocation="https://timefold.ai/xsd/solver https://timefold.ai/xsd/solver/solver.xsd"> <daemon>true</daemon> ... </solver>Do not forget to call

Solver.terminateEarly()when your application needs to shutdown to avoid killing the solver thread unnaturally. -

Subscribe to the

BestSolutionChangedEventto process new best solutions found by the solver thread.A

BestSolutionChangedEventdoes not guarantee that everyProblemChangehas been processed already, nor that the solution is initialized and feasible. -

To ignore

BestSolutionChangedEvents with such invalid solutions, do the following:-

Java

public void bestSolutionChanged(BestSolutionChangedEvent<VehicleRoutePlan> event) { if (event.isEveryProblemChangeProcessed() // Ignore infeasible (including uninitialized) solutions && event.getNewBestSolution().getScore().isFeasible()) { ... } } -

-

Use the event’s

isNewBestSolutionInitialized()method instead ofScore.isFeasible()to only ignore uninitialized solutions, but do accept infeasible solutions too.

5. Responding to adhoc changes

With real-time planning, we can respond to a continuous stream of external changes. However, it is often necessary to respond to adhoc changes too, for example when a call center operator needs to arrange an appointment with a customer. In such cases, it is not necessary to use the full power of real-time planning. Instead, immediate response to the customer and a selection of available time windows are more important. This is where Assignment Recommendation API comes in.

The Assignment Recommendation API allows you to quickly respond to adhoc changes, while providing a selection of the best available options for fitting the change in the existing schedule. It doesn’t use the full local search algorithm. Instead, it uses a simple greedy algorithm together with incremental calculation. This combination allows the API to find the best possible fit within the existing solution in a matter of milliseconds, even for large planning problems.

Once the customer has accepted one of the available options and the change has been reflected in the solution, the full local search algorithm can be used to optimize the entire solution around this change. This would be an example of continuous planning.

5.1. Using the Assignment Recommendation API

The Assignment Recommendation API requires an entity to be evaluated for assignment:

EmployeeSchedule employeeSchedule = ...; // Our planning solution.

Shift unassignedShift = new Shift(...); // A new shift needs to be assigned.

employeeSchedule.getShifts().add(unassignedShift);If the entity is unassigned, then it must be the only unassigned entity in the planning solution.

The SolutionManager is then used to retrieve the recommended assignments for this entity:

SolutionManager<EmployeeSchedule, HardSoftScore> solutionManager = ...;

List<RecommendedAssignment<Employee, HardSoftScore>> recommendations =

solutionManager.recommendAssignment(employeeSchedule, unassignedShift, Shift::getEmployee);Breaking this down, we have:

-

employeeSchedule, the planning solution. -

unassignedShift, the uninitialized entity, which is part of the planning solution. -

Shift::getEmployee, a function extracting the planning variable from the entity, also called a "proposition function". -

List<RecommendedAssignment<Employee, HardSoftScore>>, the list of recommended employees to assign to the shift, in the order of decreasing preference. Each recommendation contains the employee and the difference in score caused by assigning the employee to the shift. This difference has the full explanatory power of score analysis.

This list of recommendations can be used to present the operator with a selection of available options, as it is fully serializable to JSON and can be sent to a web browser or mobile app. The operator can then select the best available recommendation and assign the employee to the shift, represented here by the necessary backend code:

RecommendedAssignment<Employee, HardSoftScore> bestRecommendation = recommendations.get(0);

Employee bestEmployee = bestRecommendation.proposition();

unassignedShift.setEmployee(bestEmployee);If required, continuous planning can be used to optimize the entire solution afterwards.

|

Assignment Recommendation API requires the |

5.2. Using mutable types in the proposition function

In the previous example, we used a simple proposition function that extracts the planning variable from the entity. However, it is also possible to use a more complex proposition function that extracts the entire planning entity, or any values that will mutate as the solver tries to find the best fit. In that case, there are some caveats to consider.

The solver will try to find the best fit for the uninitialized entity, and it will start from the solution it received on input. Before trying the next value to assign, it will first return to that original solution. The consequence of this is that if our proposition function returns any values that change during this process, those changes will also affect the previously processed propositions. In other words, if we decide to return the entire entity from the proposition function, we will find that each of the final recommendations is the same. And because the solver will return to the original solution after trying the last value, the final recommendation will be unassigned, defeating the purpose of the API. Consider the following example:

SolutionManager<EmployeeSchedule, HardSoftScore> solutionManager = ...;

List<RecommendedAssignment<Shift, HardSoftScore>> recommendations =

solutionManager.recommendAssignment(employeeSchedule, unassignedShift, shift -> shift);The proposition function (shift → shift) returns the entire Shift entity.

Because of the behavior described above,

every RecommendedAssignment in the recommendations list will point to the same unassignedShift,

and its employee variable will be null.

This is not what we want,

because none of the RecommendedAssignment instances give us the Employee we need to assign to the shift.

To avoid this, the proposition function should preferably return a value that does not change during the process, such as the planning variable instead of the entire entity. If it’s necessary to return a value that could be mutated by the solver, we should make a defensive copy.

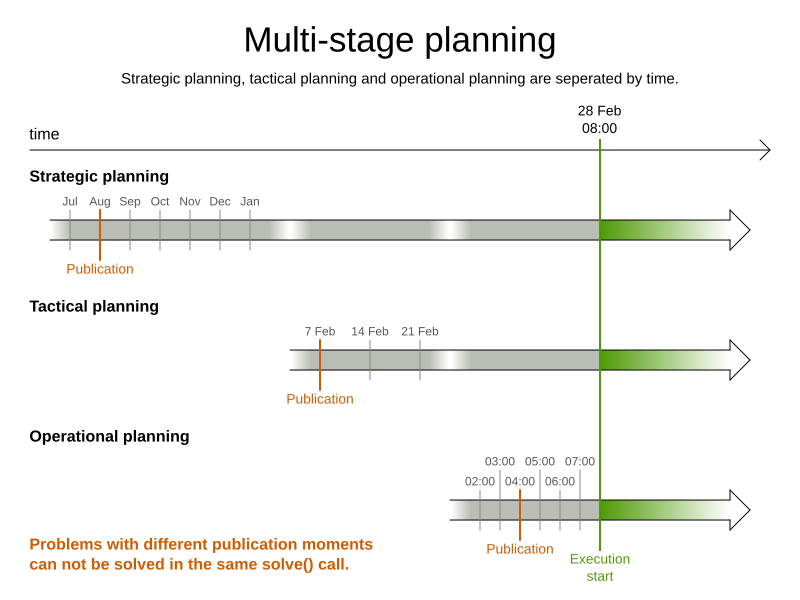

6. Multi-stage planning

In multi-stage planning, complex planning problems are broken down in multiple stages. A typical example is train scheduling, where one department decides where and when a train will arrive or depart and another department assigns the operators to the actual train cars or locomotives.

Each stage has its own solver configuration (and therefore its own SolverFactory):

Planning problems with different publication deadlines must use multi-stage planning. But problems with the same publication deadline, solved by different organizational groups are also initially better off with multi-stage planning, because of Conway’s law and the high risk associated with unifying such groups.

Similarly to Partitioned Search, multi-stage planning leads to suboptimal results. Nevertheless, it might be beneficial in order to simplify the maintenance, ownership, and help to start a project.

Do not confuse multi-stage planning with multi-phase solving.